How to Visit the Temples of Karnak

The great Temple of Amun seemingly recedes towards infinity in an overwhelming succession of pylons, courts, columned halls, obelisks and colossi, spanning some thirteen centuries of ancient history. Half-buried in silt for as long again, the ruins were subsequently squatted by fellaheen before being cleared by archeologists in the mid-nineteenth century. Ever since then, the temple has been undergoing slow but systematic restoration, epigraphic study and (in some places) excavation.

Since map-boards were installed, it’s become easier to grasp the temple’s convoluted layout; the ruins get denser and more jumbled the further in you go. The temple’s main axis is perpendicular to the Nile, with a subsidiary axis running parallel to the river, the two of them forming a T-shaped whole.

It’s worth following the main axis all the way back to the Festival Hall, and at least seeing the Cache Court of the subsidiary axis. A break for refreshments by the lake is advisable if your itinerary includes the open-air museum or the Temple of Khonsu, off the main circuit.

Entering the temple

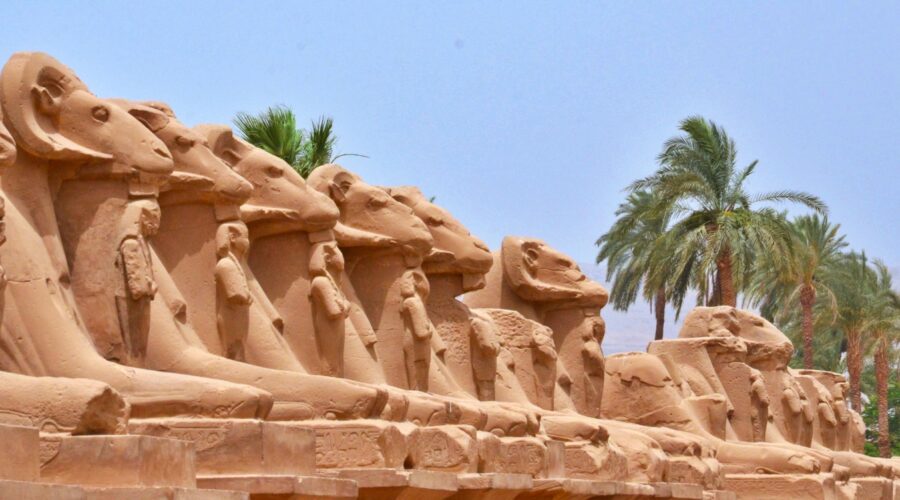

Walking towards the Precinct of Amun and crossing over a dry moat, you’ll pass the remains of an ancient dock, from where Amun sailed for Luxor Temple during the Opet festival. Before being loaded aboard a full-size boat, his sacred boat rested in the small chapel to the right, which was erected (and graffitied by mercenaries) during the brief XXIX Dynasty. Beyond lies a short Processional Way flanked by ram-headed sphinxes ⇑ (after Amun’s sacred animal) enfolding statues of Ramses II, which once joined the main avenue linking the two temples.

The First Pylon and Forecourt

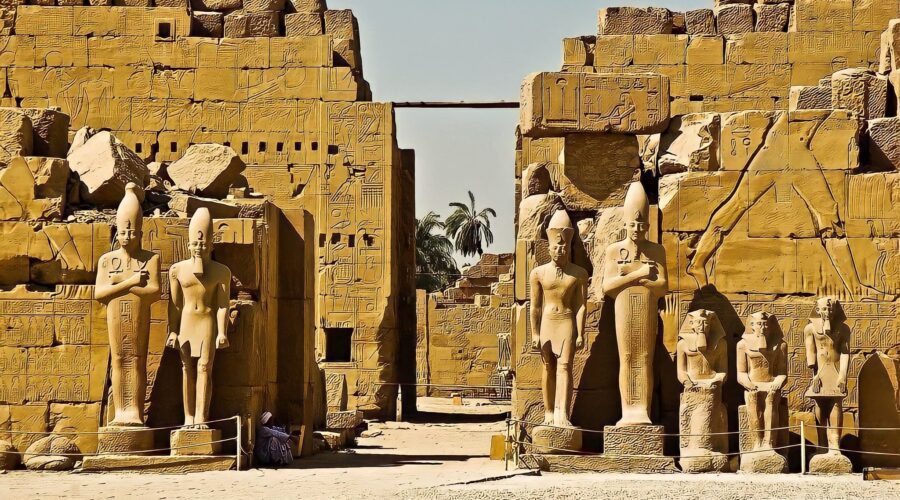

At the end of the Processional Way rises the gigantic First Pylon, whose yawning gateway exposes a vista of receding portals, dwarfing all who walk between them. ⇑ The 43-metre-high towers, composed of regular courses of sandstone masonry, are often attributed to the Nubian and Ethiopian kings of the XXV Dynasty, but may have been erected as late as the XXX Dynasty (when Nectanebo I added the enclosure wall). Although the northern tower is unfinished and neither is decorated, their 130-metre width makes this the largest pylon in Egypt.

The Forecourt

It is another late addition, enclosing three earlier structures. In the centre stands a single papyriform pillar from the Kiosk of Taharqa ⇑ (an Ethiopian king of the XXV Dynasty), thought to have been a roofless pavilion where Amun’s effigy was placed for its revivifying union with the sun at New Year. Off to the left stands the so-called Shrine of Seti II, actually a way station for the sacred boat of Amun, Mut and Khonsu, built of grey sandstone and rose granite.

The Temple of Ramses III and Second Pylon

The first really impressive structure in the precinct is the columned Temple of Ramses III, which also held the Theban Triad sacred boats during processions. Beyond its pylon, flanked by two colossi, is a festival hall with mummiform pillar statues behind which are carvings of the annual Optet festival of Amun-Min.⇑

Though the pink granite Colossus of Ramses II beside the vestibule to the Second Pylon is an immediate attention-grabber, it’s worth detouring round the side of his temple to pass through the Bubastite Portal, named after the XXII Dynasty that hailed from Bubastis in the Delta. En route you’ll pass a fish-shaped aperture in the Second Pylon, where in 1820 Henri Crevier uncovered a host of statues and blocks from the demolished Aten Temple (including the colossi of Akhenaten in the Luxor and Cairo museums), which Horemheb used as in-fill for his pylon.

Pass through the Portal and turn left to find the Shoshenq relief, commemorating the triumphs of the XXII Dynasty Pharaoh Shoshenq. Traditionally, scholars have identified him as the biblical Shishak (I Kings 14:25–26) who plundered Jerusalem in 925 BC, thus establishing a crucial link between the chronologies of Ancient Egypt and the Old Testament – an orthodoxy challenged by David Rohl’s book, A Test of Time. Although Shoshenk’s figure is almost invisible, you can still see Amun, presiding over the slaughter of Rheoboamite prisoners in Palestine. The scenes further along the wall are best seen after visiting the Great Hypostyle Hall.

To reach this, return to the forecourt and pass through the Second Pylon, one of several jerry-built structures begun by Horemheb, the last king of the XVIII Dynasty. The cartouches ⇑ of Seti I (who completed the pylon) and Ramses I and II (Seti’s father and son) appear just inside the doorway.

The Great Hypostyle Hall

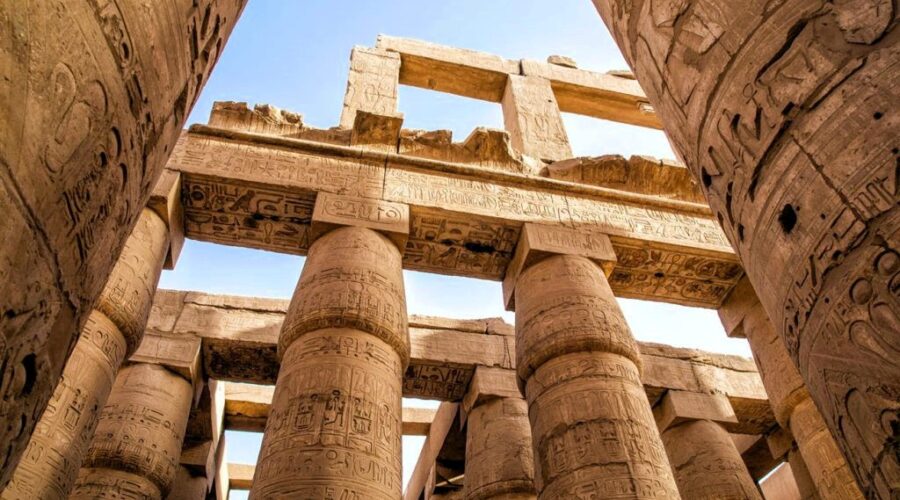

The Great Hypostyle Hall is Karnak’s glory, a forest of titanic columns covering an area of 6000 square metres – large enough to contain both St Peter’s Cathedral in Rome and St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Its grandeur is best appreciated early in the morning or late in the afternoon, when diagonal shadows enhance the effect of the columns. In pharaonic times the hall was roofed with sandstone slabs, its gloom interspersed by sunbeams falling through windows above the central aisle.

The hall probably began as a processional avenue of twelve or fourteen columns, each 23m high and 15m round (requiring six people with outstretched arms to encircle their girth). To this, Seti I and Ramses II added 122 smaller columns in two flanking wings, plus walls and a roof. All the columns consist of semi-drums, fitted together without mortar. Their carvings show the king making offerings to Theban deities, most notably Amun, who frequently appears in a sexually aroused state. Some Egyptologists believe that the temple priestesses kept Amun happy by masturbating his idol, and that the pharaoh did his bit to ensure the fertility of Egypt by ejaculating into the Nile during the Opet festival.

Similar cult scenes decorate the side and end walls of the hall, which manifest two styles of carving. While Seti adorned the northern wing with bas-reliefs, Ramses II favored cheaper sunk reliefs for the southern wing. You can compare the two styles on the Hypostyle Hall’s entrance wall, which features nearly symmetrical scenes of Amun’s sacred boat procession. ⇑

In Seti’s northern wing, the procession begins on the north wall with a depiction of Amun’s sacred boat, initially veiled, then revealed. Thoth inscribes the duration of Seti’s reign on the leaves of a sacred Persea tree just beyond the doorway. By walking out through this door you’ll come upon Seti I’s battle scenes, whose weathered details are best observed in the early morning or late afternoon. One section relates the capture of Kadesh from the Hittites in Syria (lower rows), and Seti’s triumphs over the Libyans. Depicted elsewhere are his campaigns against the Shasu of southern Palestine and the storming of Pa-Canaan, which the Egyptians “plundered with every evil”.

Returning to the Hypostyle Hall, you can find similar reliefs commissioned by Ramses II in the southern wing, retaining traces of their original colours. Beyond the sacred boat procession on the inner wall, Ramses is presented to Amun and enthroned between Wadjet and Nekhbet, while Thoth and Horus adjust his crowns. On the outer wall are Ramses II’s battle scenes, starting with the second Battle of Kadesh (c.1300 BC). Though scholars reckon it was probably a draw, Ramses claimed total victory over the Hittites. The text of their peace treaty (the earliest such document known) appears on the outer wall of the Cachette Court.

This is known as the Ashkelon Wall after one of the four battle scenes flanking the treaty; another may depict a fight with the Israelites. Rohl argues that the enemy chariots in this scene contradict established chronology, since the Israelites didn’t develop them until King Solomon’s reign, but Ramses is conventionally supposed to have been the Pharaoh of the Oppression in the time of Moses, centuries earlier.

The Third Pylon

Beyond the XIX Dynasty Hypostyle Hall lies an extensive section of the precinct dating from the XVIII Dynasty. The Third Pylon that forms its back wall was originally intended by Amenhotep III to be a monumental gateway to the temple. Like Horemheb forty years later, he demolished earlier structures to serve as core filler for his pylon. Removed by archeologists, these blocks are now displayed – partly reassembled – in the open-air museum. Two huge reliefs of Amun’s sacred boat appear on the far wall of the pylon.

The narrow court between the Third and Fourth pylons was once ennobled by four Tuthmosid obelisks. The stone bases near the Third Pylon belonged to a pair erected by Tuthmosis III, chunks of which lie scattered around. Of the pink-granite pair erected by Tuthmosis II, one still stands 23m high, with an estimated weight of 143 tonnes. ⇑ Once tipped with glittering electrum, the finely carved obelisk was later appropriated by Ramses IV and VI, who added their own cartouches.

The fourth, fifth and sixth pylons

At this stage it’s best to carry on through the Fourth Pylon rather than get sidetracked into the Cachette Court on the temple’s secondary axis. Beyond the pylon are numerous columns which probably formed another hypostyle hall, dominated by the rose-granite Obelisk of Hatshepsut, the only woman to rule as a pharaoh. To mark her sixteenth regnal year, Hatshepsut had two obelisks quarried in Aswan and erected at Karnak, a task completed in seven months. ⇑The standing obelisk is more than 27m high and weighs 320 tons, with a dedicatory inscription running its full height. Its fallen mate has broken into sections, now dispersed around the temple.

The fallen obelisk’s carved tip can be examined near Osireion and Sacred Lake. On the way there, you’ll pass a granite bas-relief of Amenhotep II target-shooting from a moving chariot, protruding from the Fifth Pylon. Built of limestone, this pylon is attributed to Hatshepsut’s father, Tuthmosis I.

Though the Sixth Pylon has largely disappeared, a portion of either side of the granite doorway remains. Its outer face is known as the Wall of Records after its list of peoples conquered by Tuthmosis III: Nubians to the right, Asiatics to the left. Beyond the latter is a text extolling the king’s victory at Megiddo (Armageddon) in 1479 BC. By organizing tribute from his vanquished foes rather than simply destroying them, Tuthmosis III was arguably the world’s first imperialist.

Around the Sanctuary

The section beyond the Sixth Pylon gets increasingly confusing, but a few features are unmistakable. Ahead stand a pair of square-sectioned heraldic pillars, their fronts carved with the lotus and papyrus of the Two Lands, their sides showing Amun embracing Tuthmosis III. ⇑ On the left are two Colossi of Amun and Amunet, dedicated by Tutankhamun (whose likeness appears with them) to mark the restoration of orthodoxy after the “heretical” Amarna Period. There’s also a seated statue of Amenhotep II.⇑

Next comes a granite Sanctuary built by Philip Arrhidaeus, the cretinous half-brother of Alexander the Great, on the site of a Tuthmosis-era shrine which similarly held Amun’s sacred boat. The interior bas-reliefs show Philip making offerings to Amun in his various aspects, topped by a star-spangled ceiling.⇑

Around to the left of the Sanctuary and further back is a wall inscribed with Tuthmosis III’s victories, which he built to hide a wall of reliefs by Queen Hatshepsut, now removed to another room. Hatshepsut’s Wall has reopened after lengthy restoration, as has the facing portion, where Tuthmosis replaced her image by offering tables or bouquets, and substituted his father’s and grandfather’s names for her cartouches (see Hatshepsut).

Beyond here lies an open space or Central Court, thought to mark the site of the original temple of Amun built in the XII Dynasty, whose weathered alabaster foundations poke from the pebbly ground.

The Jubilee Temple of Tutmosis III

At the rear of the Central Court rises the Jubilee Temple of Tuthmosis III, a personal cult shrine in Amun’s backyard. As at Saqqara during the Old Kingdom, the Theban kings periodically renewed their temporal and spiritual authority with Heb-Sed, or jubilee festivals. The original entrance is flanked by reliefs and broken statues of Tuthmosis in Heb-Sed regalia. ⇑ A left turn brings you into the Festival Hall, with its unusual tentpole-style columns, their capitals adorned with blue-and-yellow chevrons. During Christian times the hall was used as a church, hence the haloed saints on some of the pillars.

A chamber off the southwest corner contains an eroded replica of the Table of Kings (the original is in the Louvre), depicting Tuthmosis making offerings to previous rulers – Hatshepsut is omitted from the roll call.

The Botanical Garden

The so-called Botanical Garden is a roofless enclosure containing painted reliefs of plants and animals which Tutmosis encountered on his campaigns in Syria. Across the way is a roofed chamber decorated by Alexander the Great, who appears before Amun and other deities. The Chapel of Sokar constitutes a miniature temple to the Memphis god of darkness, juxtaposed against a (now inaccessible) shrine to the sun. A further suite of rooms is dedicated to Tutmosis.

Chapels of the Hearing Ear

Excluded from Amun’s Precinct and lacking a direct line to the Theban Triad, the inhabitants of Thebes used intermediary deities to transmit their petitions. These lesser deities rated their own shrines, known as Chapels of the Hearing Ear (sometimes actually decorated with carved ears), which straddled the temple’s enclosure wall, presenting one face to the outside world. At Karnak, however, they became steadily less approachable and were finally surrounded by the present enclosure wall.

Directly behind the Jubilee Temple is a series of chapels built by Tuthmosis III, centred upon a large alabaster statue of the king and Amun. Further east lie the ruined halls and colonnades of a Temple of the Hearing Ear built by Ramses II. Behind this stands the pedestal of the tallest obelisk known (31m), which Emperor Constantine had shipped to Rome and erected in the Circus Maximus; it was later moved to Lateran Square, hence its name, the Lateran Obelisk. As the Ancient Egyptians rarely erected single obelisks, it was probably intended to be accompanied by the Unfinished Obelisk that lies in a quarry outside Aswan, abandoned after the discovery of flaws in the rock.

Around the Sacred Lake

A short walk from Hatshepsut’s Obelisk or the Cache Court brings you to Karnak’s Sacred Lake, which looks about as holy as a municipal boating pond, with the grandstand for the Sound and Light Show at the far end. The main attraction is a shady (and very pricey) café where you can take a break from touring the complex and imagine the scene in ancient times. At sunrise, Amun’s priests would take a sacred goose from the fowl-yards which now lie beneath the mound to the south of the lake and set it free on the waters. As at Hermopolis, the goose or Great Cackler was credited with laying a cosmic egg at the dawn of Creation; but at Karnak the Great Cackler was identified with Amun rather than Thoth.

During the Late Period, Pharaoh Taharqa added a subterranean Osireion, linking the resurrection of Osiris with that of the sun. Nearby, a giant scarab beetle represents Khepri, the reborn sun at dawn.

The north–south axis

The temple’s north–south axis is sparser and less variegated than the main section, so if time is limited there’s little reason to go beyond the Seventh Pylon. The Gate of Ramses IX, at the southern end of the court between the Third and Fourth pylons, gives access to this wing of the temple, which starts with the Cachette Court.

The Cachette Court gets its title from the discovery of a buried hoard of statues early in the twentieth century. Nearly 17,000 bronze statues and votive tablets, and 800 figures in stone, seem to have been cached in a “clearance” of sacred knick-knacks during Ptolemaic times. The finest statues (dating from the Old Kingdom to the Late Period) are now in the Luxor and Cairo museums. The court’s northwest corner incorporates a mass of hieroglyphics known as the Epic of Pentaur, which recaps the battles of Ramses II depicted on the outside of the Great Hypostyle Hall. Diagonally across the court are an eighty-line inscription by Merneptah and a copy of the Israel Stele that’s in Cairo, which contains among a list of conquests the only known pharaonic reference to Israel: “Israel is crushed, it has no more seed”. Rohl argues that the stele has been misread and really relates the achievements of Merneptah’s father and grandfather, Ramses II and Seti I.

More proof of the complexities of Egyptology is provided by the Seventh Pylon, which was built by Tuthmosis III, but decorated and usurped during the XIX Dynasty, a century or so later, when the cartouches on its door jambs were altered to proclaim false ownership. It is fronted by seven statues of Middle Kingdom pharaohs, salvaged from pylon cores. On the far side are the lower portions of two Colossi of Tuthmosis III.