What to See at Luxor Temple

Luxor Temple is huge in scale — it once housed a village within its walls.

It has several pylons (monumental gateways) that are some 70 yards long.

The first pylon is over 70 feet high, fronted by massive statues and several obelisks.

There are several open areas, once used for various forms of worship but now empty. Later additions include a shrine to Alexander the Great, a Roman sanctuary, and an Islamic shrine to a 13th-century holy man.

Entrance to the temple was – and still is – from the north, where a causeway lined by sphinxes that once led all the way to Karnak begins. This road, known as the Sacred Way or Avenue of Sphinxes, was a later addition, dating from the time of Nectanebo I in the 30th Dynasty.

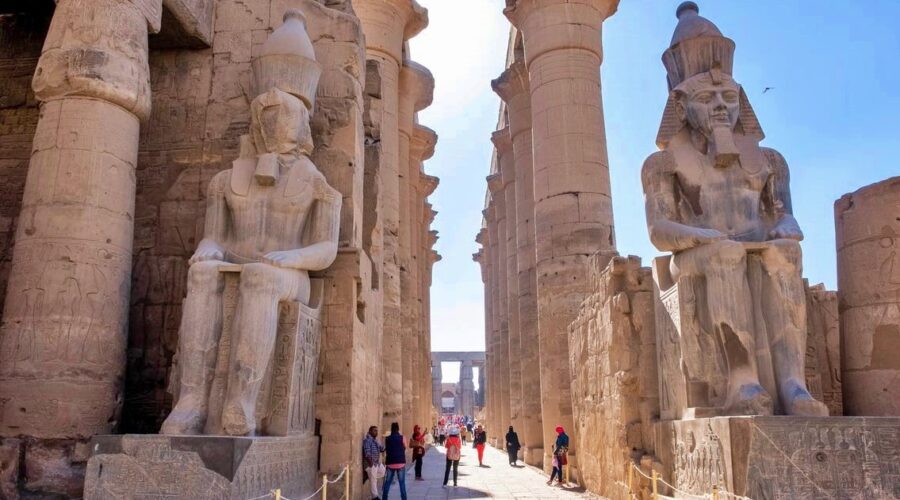

The temple proper begins with the 24-metre-high First Pylon, built by Ramesses II. The pylon was decorated with scenes of Ramesses’s military triumphs (particularly the Battle of Kadesh); later pharaohs, particularly those of the Nubian and Ethiopian dynasties, also recorded their victories there.

This main entrance to the temple complex was originally flanked by six colossal statues of Ramesses – four seated, and two standing – but only two seated statues have survived.

Also surviving is a 25-metre-tall pink granite obelisk. It was one of a matching pair until 1835 when the other one was taken to Paris where it now stands in the center of the Place de la Concorde.

The pylon gateway leads into a peristyle courtyard, also built by Ramesses II. This area and the pylon were built at an oblique angle to the rest of the temple, presumably to accommodate the three pre-existing barque shrines located in the northwest corner.

It is atop the columns of this courtyard that the Abu Haggag Mosque was built on the eastern side, a doorway leads out into thin air some 8 meters above the ground.

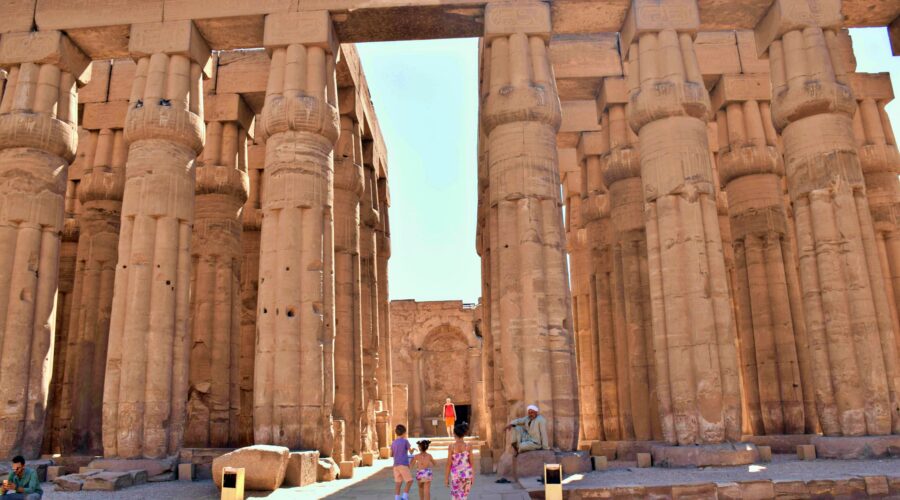

After the peristyle courtyard comes the processional colonnade built by Amenhotep III – a 100-metre corridor lined by 14 papyrus-capital columns. Friezes on the wall describe the stages in the Opet Festival, from sacrifices at Karnak at the top left, through Ammon’s arrival at Luxor at the end of that wall and concluding with his return on the opposite side. The decorations were put in place by Tutankhamun: the boy pharaoh is depicted, but his name has been replaced with that of Horemheb.

Beyond the colonnade is another peristyle courtyard, which also dates back to Amenhotep’s original construction. The best-preserved columns are on the eastern side, where some traces of original color can be seen. The southern side of this courtyard is made up of a 32-column hypostyle court that leads into the inner sanctums of the temple.

The inner sanctums begin with a dark antechamber. Of particular interest here are the Roman stuccoes that can still be seen atop the Egyptian carvings below; in Roman times this area served as a chapel, where local Christians were offered a final opportunity to renounce their faith and embrace the pagan state religion.

Further in stands a Barque Shrine for use by Amun, built by Alexander, with the final area being the private quarters of the gods and the Birth Shrine of Amenhotep III. The latter features detailed wall paintings depicting the pharaoh’s claim to have been fathered by Amun, and therefore of divine descent.

A cache of 26 New Kingdom statues was found under the floor in the inner sanctum area in 1989 – hidden away by pious priests, presumably, at some moment of internal upheaval or invasion. These splendid pieces are now on display at the nearby Luxor Museum